SPIRIT IS A BONE

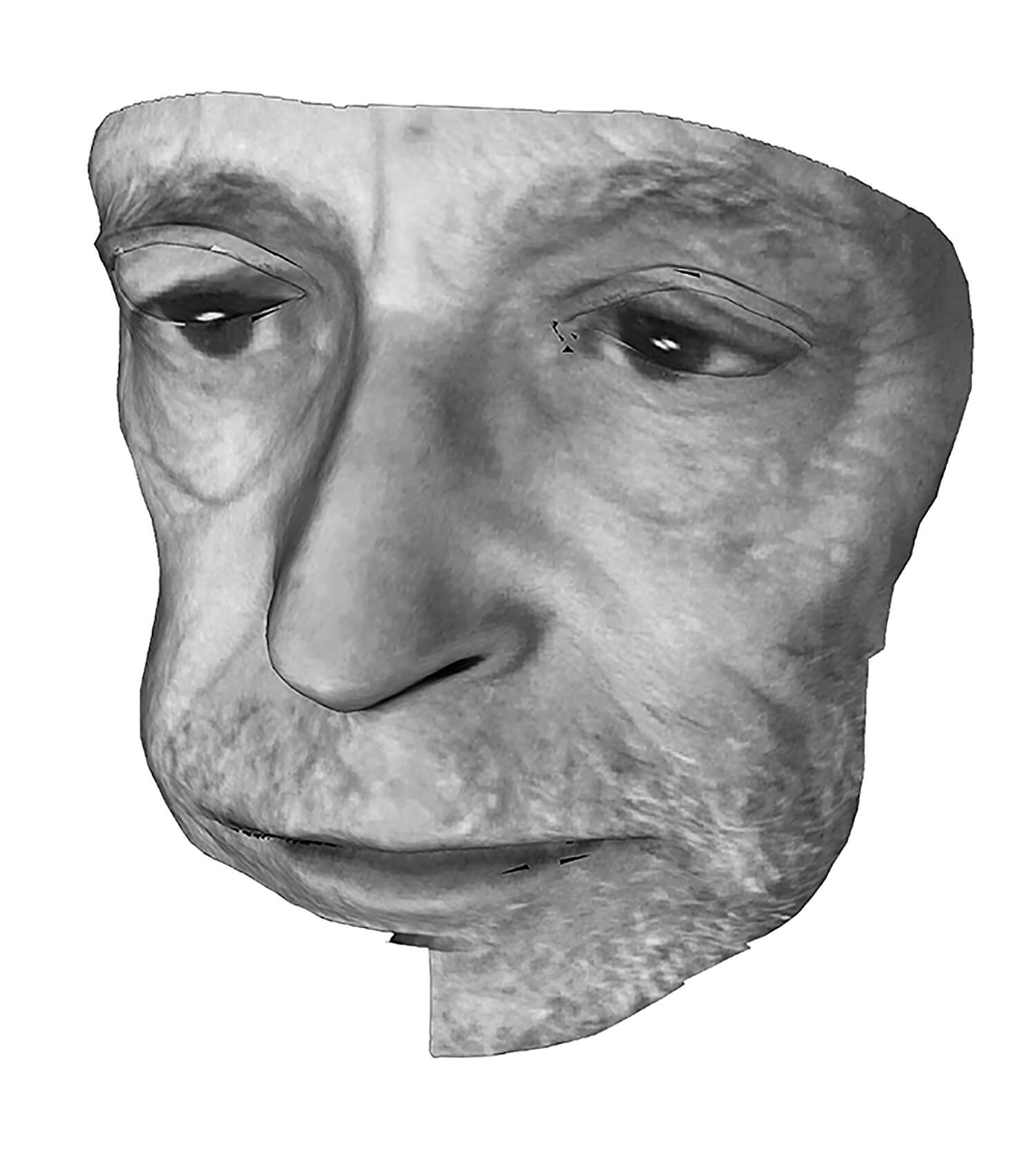

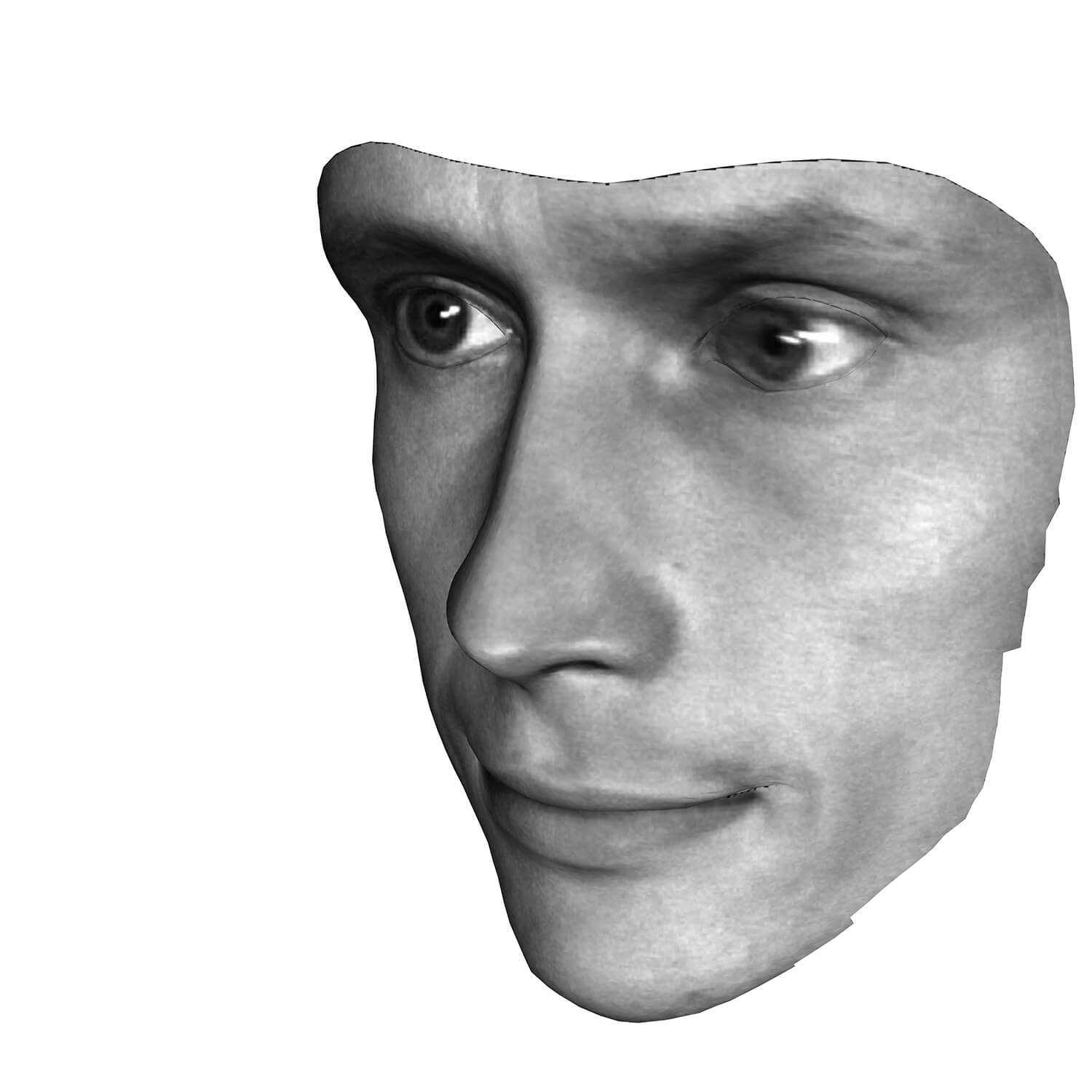

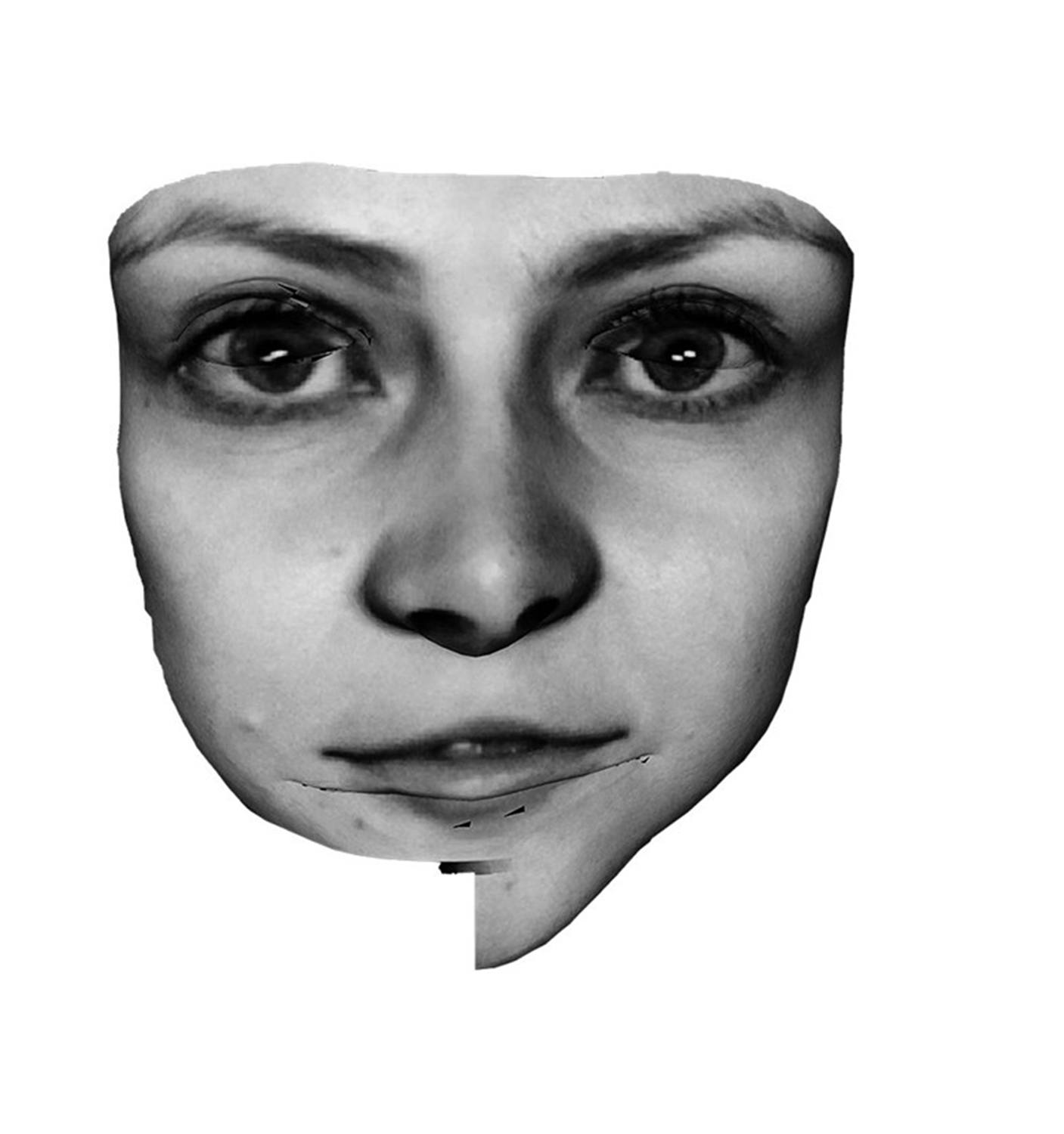

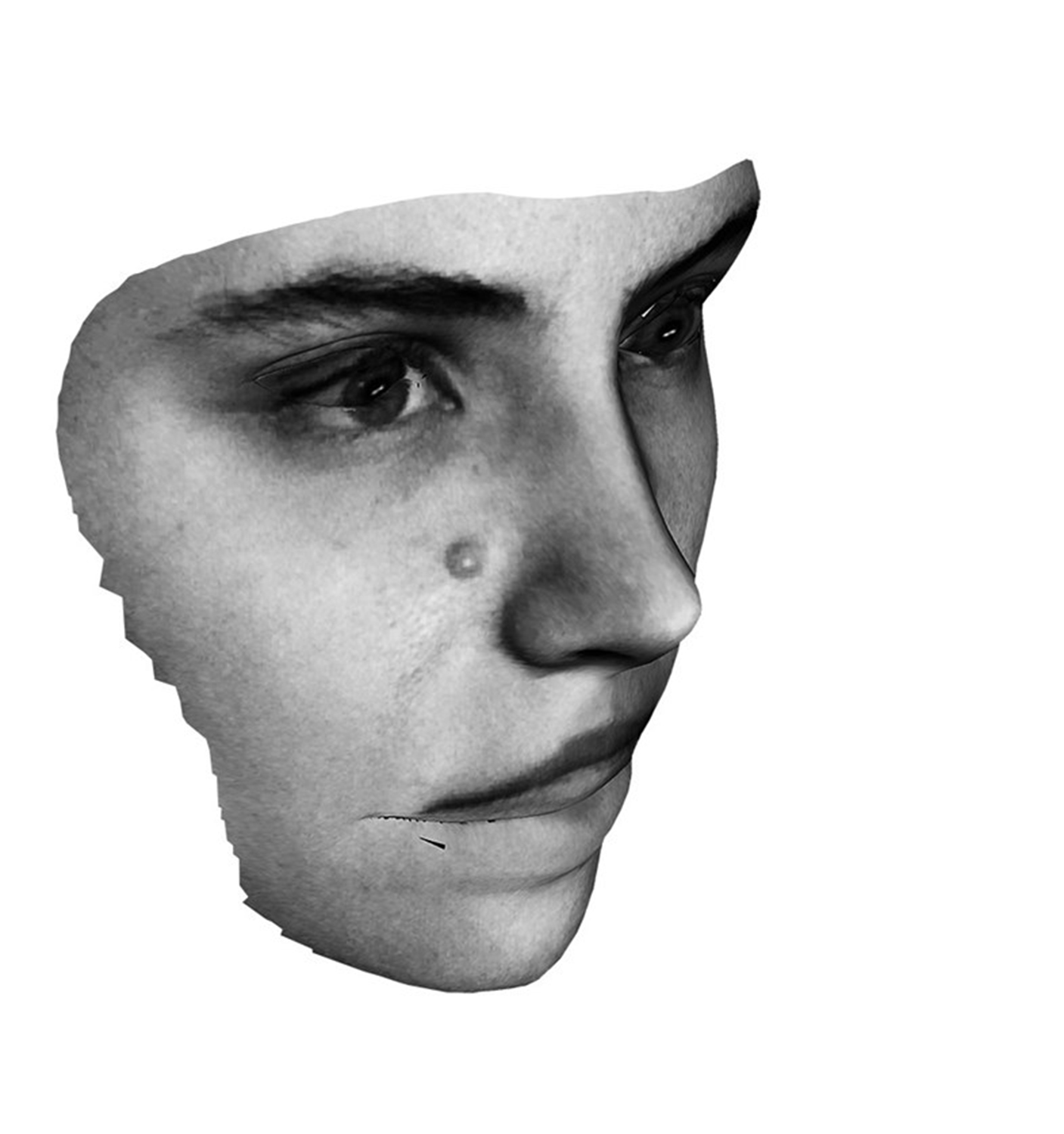

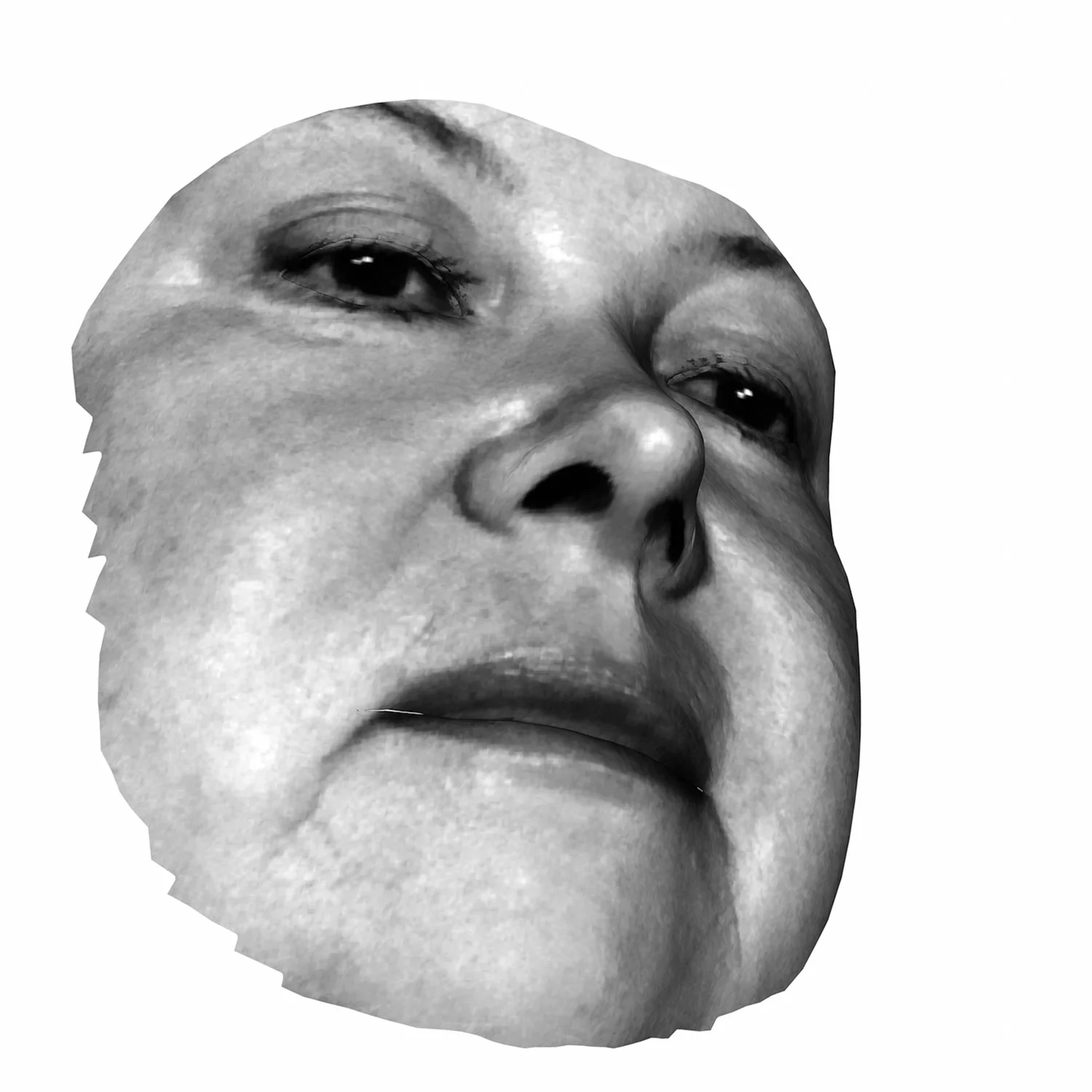

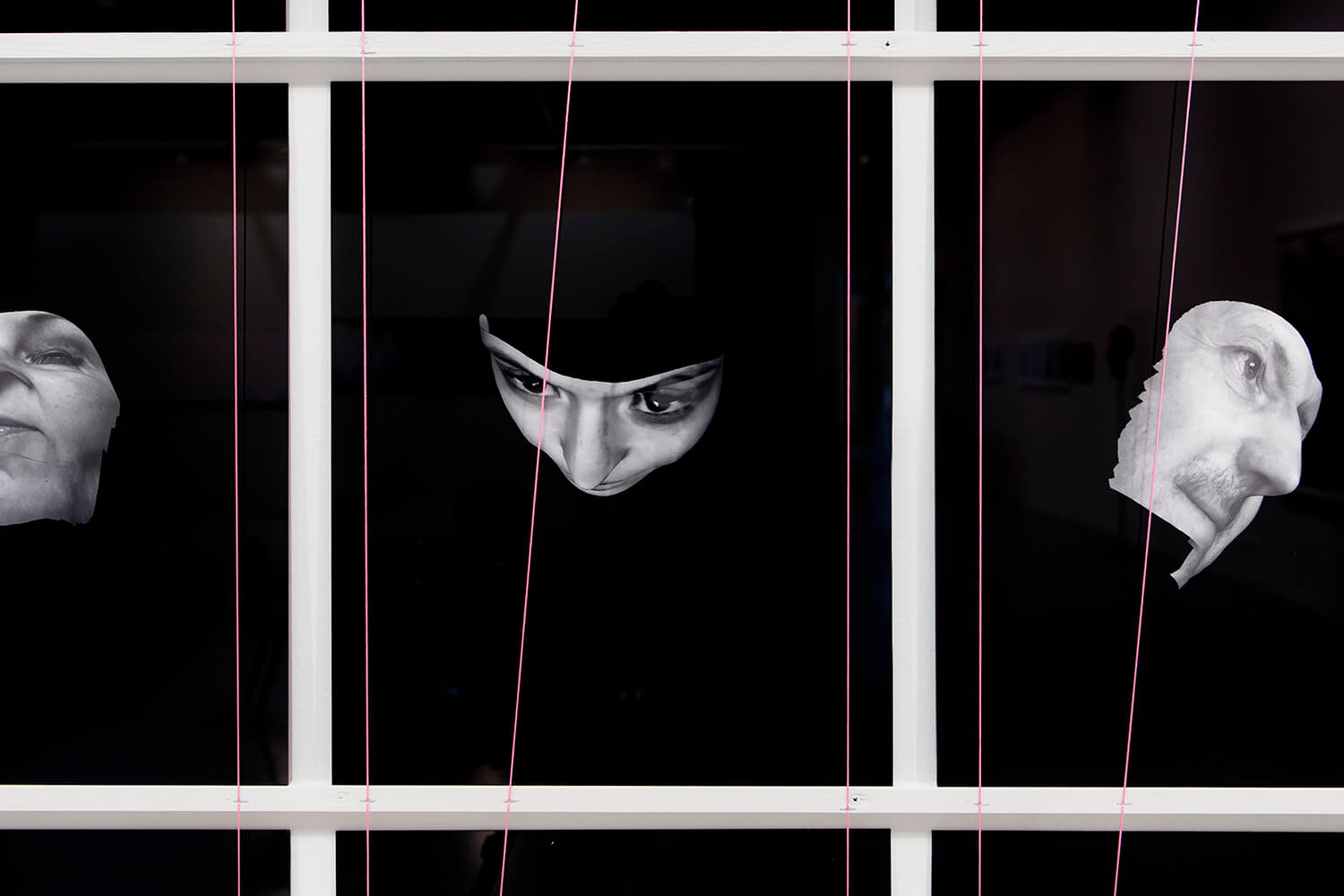

This series of portraits, which includes Pussy Riot member Yekaterina Samutsevic and many other Moscow citizens, were created by a machine: a facial recognition system recently developed in Moscow for public security and border control surveillance. The result is more akin to a digital life mask than a photograph; a three-dimensional facsimile of the face that can be easily rotated and closely scrutinised.

What is significant about this camera is that it is designed to make portraits without the co-operation of the subject; four lenses operating in tandem to generate a full frontal image of the face, ostensibly looking directly into the camera, even if the subject himself is unaware of being photographed.

The system was designed for facial recognition purposes in crowded areas such as subway stations, railroad stations, stadiums, concert halls or other public areas but also for photographing people who would normally resist being photographed. Indeed any subject encountering this type of camera is rendered passive, because no matter which direction he or she looks, the face is always rendered looking forward and stripped bare of shadows, make-up, disguises or even poise.

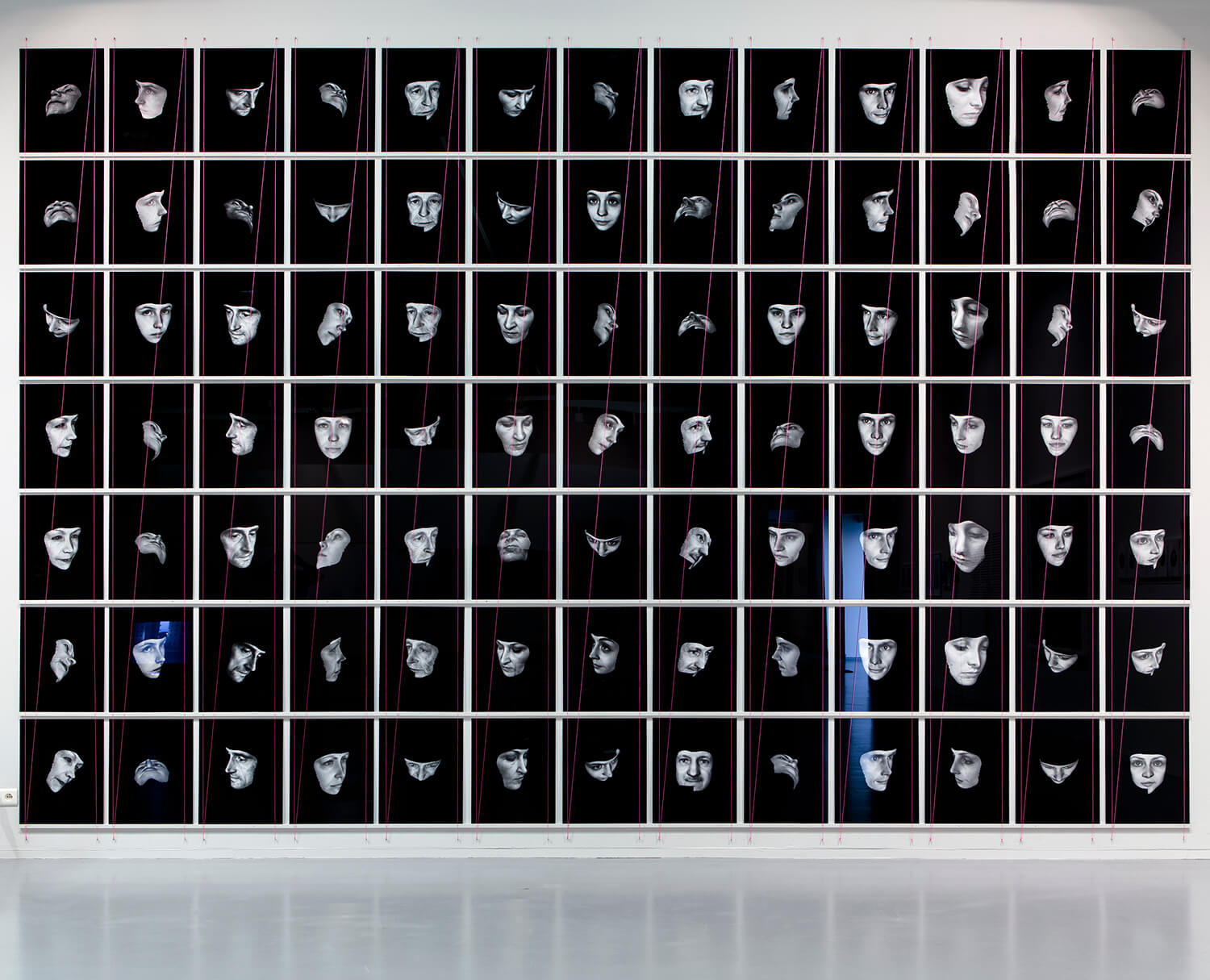

Co-opting this device, Broomberg & Chanarin have constructed their own taxonomy of portraits in contemporary Russia that rely heavily on the oeuvre of two 20th Century German artists. August Sander produced over 300 portraits of archetypal German workers during the Weimar Republic – from the baker to the philosopher to the revolutionary. His project, to create a comprehensive archive of society, was conceptually and formally rigorous. His subjects are positioned centre frame. Always looking into camera. Always heroic in relation to the lens. But the result, retrospectively viewed through the lens of the 2nd World War becomes unexpectedly melancholic, even sinister.

Sander’s contemporary, Helmar Lerski, also categorised his subjects according to profession. Lerski however rejected the singular, heroic, full body portrait. Instead he insisted on repetitive close-ups that convey a powerful sense of claustrophobia; and always multiple views of the same faces shown from different viewpoints. Unlike Sander's humanistic approach, Lerski insisted that you could tell nothing from the surface of the skin.

Echoing both Sander's and Lerski’s projects, Broomberg & Chanarin have made a series of portraits cast according to professions. But their portraits are produced with this new technology, with little if any human interaction. They are low resolution and fragmented. The success of these images are determined by how precisely this machine can identify its subject: the characteristics of the nose, the eyes, the chin, and how these three intersect. Nevertheless they cannot help being portraits of individuals, struggling and often failing to negotiate a civil contract with state power.

Download 'The Bone Cannot Lie', a text formed from a conversation between Eyal Weizman and the artists Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin on 27 September 2015, and featured in their book, Spirit is a bone, published by MACK, 2015

Interview in Guardian Newspaper with Broomberg and Chanarin

Related article from May 2014 edition of Modern Painters