BANDAGE THE KNIFE NOT THE WOUND

Over one trillion images were produced in the world last year, mostly distributed on social media; mostly tools of self-promotion and self-flagellation.

For the past twenty years, Broomberg and Chanarin have engaged in a forensic and paranoid interrogation of the medium of photography in search of its source code; the cultural, emotional, political and financial currency of photographs.

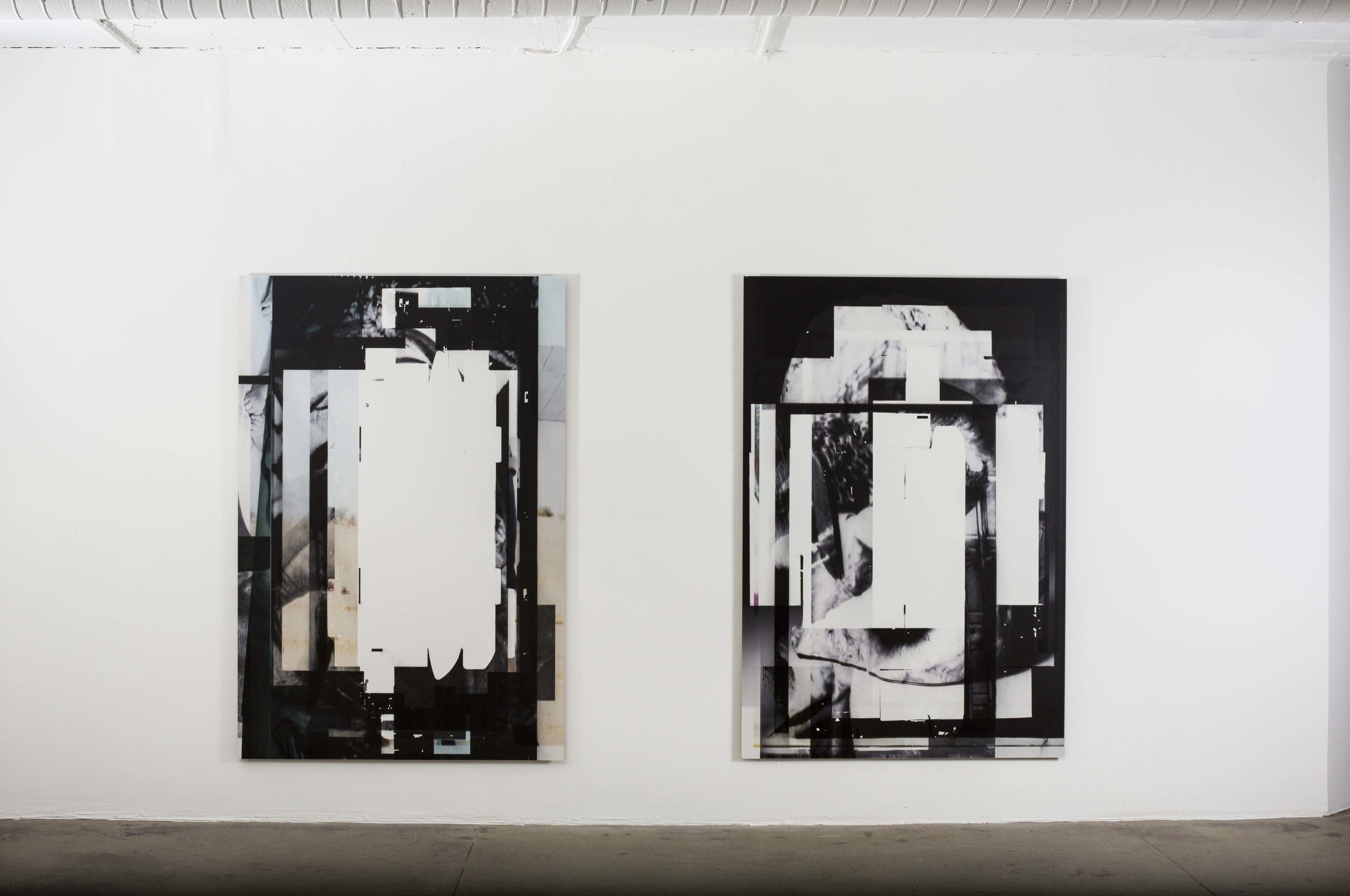

For Bandage the knife not the wound, the artists reflect on their precarious sense of place and belonging to their homeland (South Africa), to photography and to each other by turning to the handful of images that remain meaningful to them. These include a profile of Pasolini’s head taken in the morgue, an anonymous figure falling through space, scanned from a police instruction manual and David Scherman’s photograph of Lee Miller in Hitler’s bath - images that refuse to be deleted and that resurface again and again in their exchanges.

Turning to their own archives, and embracing accidents and mishaps, Broomberg and Chanarin have produced a series of montages, playing a game of visual ping-pong that recalls the surrealist method exquisite corpse, where one image responds to the next. They have reproduced the results in incremental layers on the backs of unfolded cardboard boxes used for packaging photographic paper. Dissecting their images along industrial folds and perforations on this cheap, readily available material suggests something frightening about the life of images in the digital age; algorithmic, disposable and further than ever from the original.